GERM CELL TUMORS

GCTs account for approximately one-third of all pineal tumors and are histologically

identical to gonadal GCTs with a predominance in men and younger age groups. Extragonadal

GCTs (including pineal region) have a poorer prognosis than gonadal GCTs. GCTs range along

a spectrum from benign (as in teratomas, dermoids, epidermoids, and lipomas) to highly

malignant (as in choriocarcinomas, embryonal cell carcinomas, teratocarcinomas, and

endodermal sinus tumors).

Germinomas are tumors of an intermediate degree of malignancy arising from primordial germ

cells that can occur in the gonads or in midline sites in the nervous system (pineal and

suprasellar region) or body (mediastinum and sacrococcygeal region). Although

histologically identical in all sites of origin, by conventional nomenclature germinomas

in the testes are called seminomas, those in the ovaries are dysgerminomas, and those in

the CNS are germinomas (previously called atypical teratomas).

Unlike suprasellar GCTs, which show no sexual predisposition, GCTs of the pineal region

occur predominantly in males. Germinomas are most common in boys in the first or second

decade and have a propensity to seed the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways. Despite their

malignant characteristics, germinomas are exquisitely sensitive to radiotherapy and

chemotherapy; they can be cured in many patients. The presence of beta human chorionic

gonadotropin (b-hCG) in a germinoma implies a slightly worse prognosis.Embryonal cell

carcinomas, choriocarcinomas, and endodermal sinus tumors are rare but highly malignant

GCTs that may metastasize to the CSF. Choriocarcinoma contains cyto- and

syncytiotrophoblastic cells that produce b-hCG. Endodermal sinus tumors contain yolk sac

elements that produce alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). High levels of b-hCG or AFP in the CSF or

serum indicate the presence of malignant germ cell elements, and histologic confirmation

is not necessary for treatment with radiation, chemotherapy, or both . GCTs in general are

difficult to classify because 25% are of a mixed type, containing both malignant and

benign elements or several different malignant elements. Extensive specimen sampling is

necessary for accurate histologic determination. High AFP or b-hCG levels in the CSF

trigger an extensive search for malignant germ cell elements even if the pathologic

specimens suggest otherwise. Benign GCTs such as teratomas, dermoids, and epidermoids are

generally curable with surgery alone. Teratomas are composed of tissues from three germ

cell lines (endo-, ecto-, and mesoderm). Immature teratomas are a variant of this tumor

that may grow quickly and behave in a malignant fashion, including CSF seeding.

PINEAL CELL TUMORS

Pineal cell tumors arise from pineocytes and range from histologically primitive

pineoblastomas to well-differentiated pineocytomas. Attempts to correlate prognosis and

survival with either variant have been inconclusive because both may behave in a malignant

fashion, with recurring at the primary site and spreading through the CSF. Pineal cell

tumors occur in children and young adults before age 40 with no sex predominance. They are

occasionally found concurrently with retinoblastomas and may contain mixed cell types. The

pineoblastomas are considered a variant of primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Pineal cell

tumors are radiosensitive, but experience with chemotherapy is limited.

GLIOMAS

Gliomas, like GCTs, account for one-third of pineal tumors. Most are invasive and have a

prognosis comparable with astrocytomas of the brainstem. About one-third of gliomas are

low grade, cystic, and surgically curable. Anaplastic astrocytomas and glioblastomas are

less common. Oligodendrogliomas and ependymomas may also occur. Treatment of these tumors

is identical to the treatment of gliomas in other areas of the CNS.

MENINGIOMAS

Meningiomas can arise from the velum interpositum or from the tentorial edge with a higher

incidence in middle age and the elderly. They are amenable to surgical resection.

METASTASIS AND OTHER MISCELLANEOUS TUMORS

The pineal gland does not have a blood–brain barrier and, like the pituitary gland,

may be underrecognized as a possible site for CNS metastasis of systemic tumors.

Miscellaneous tumors include sarcoma, hemangioblastoma, choroid plexus papilloma,

lymphoma, and chemodectoma.

PINEAL CYSTS

Benign cysts of the pineal gland are often found incidentally on radiographic studies, and

it is important to distinguish them from cystic tumors. They are normal variants of the

pineal gland and consist of a cystic structure surrounded by normal pineal parenchymal

tissue. Radiographically they are up to 2 cm in diameter and often have some degree of

peripheral enhancement that may be a compressed normal pineal gland. Pineal cysts may be

found in 4% of all magnetic resonance images. These cysts are static anatomic variants and

need no treatment unless they become symptomatic. In one series of 53 pineal cysts, fewer

than 10% developed hydrocephalus requiring surgical intervention.

SYMPTOMS

Pineal region tumors can become symptomatic by three mechanisms: increased intracranial

pressure from hydrocephalus, direct brainstem and cerebellar compression, or endocrine

dysfunction. Headache, associated with hydrocephalus, is the most common symptom at onset

and is caused by obstruction of third ventricle outflow at the aqueduct of Sylvius. More

advanced hydrocephalus can result in papilledema, gait disorder, nausea, vomiting,

lethargy, and memory disturbance. Direct midbrain compression can cause disorders of

ocular movements such as Parinaud syndrome (paralysis of upgaze, convergence or

retraction, nystagmus, and light-near pupillary dissociation) or the Sylvian aqueduct

syndrome (paralysis of downgaze or horizontal gaze superimposed upon a Parinaud syndrome).

Either lid retraction (Collier sign) or ptosis may follow dorsal midbrain compression or

infiltration. Fourth nerve palsies with diplopia and head tilt may be seen. Reversibility

is a clue to pathogenesis; eye signs due to hydrocephalus recede promptly after

ventricular shunting. Ataxia and dysmetria can result from direct cerebellar compression.

Endocrine dysfunction is rare, usually arising from secondary effects of hydrocephalus

or tumor spread to the hypothalamic region. Diabetes insipidus occurs in less than 5% of

pineal tumors, usually with a germinoma (Fig. 57.2). The symptoms may occur early, before

any radiographic documentation of hypothalamic seeding. Although precocious puberty has

been linked historically with pineal masses, documented cases are rare. Precocious puberty

is actually precocious pseudopuberty because the hypothalamic-gonadal axis is not mature.

It occurs strictly in boys with choriocarcinomas or germinomas with syncytiotrophoblastic

cells and ectopic secretion of b-hCG. In boys, the luteinizing hormonelike effects of

b-hCG can stimulate Leydig cells to produce androgens that induce development of secondary

sexual characteristics and pseudopuberty. This phenomenon does not occur in girls with

pineal region tumors because GCTs are rare in females; also, and more important, both

luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone are necessary to trigger ovarian

estrogen production.

DIAGNOSIS

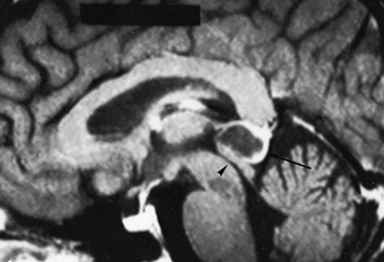

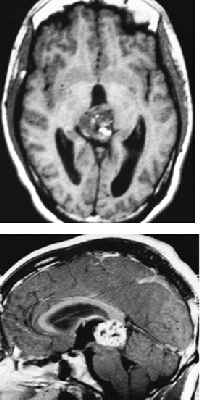

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the principal diagnostic test for pineal region

tumors. MRI with gadolinium enhancement is mandatory for all pineal tumors to determine

the presence of hydrocephalus and to evaluate tumor size, vascularity, and homogeneity. In

particular, sagittal MRI reveals the relationship of the tumor to surrounding structures

as well as possible ventricular seeding. Computed tomography is complementary but does not

provide as much information as MRI. Angiography is not performed unless a vascular anomaly

is suspected. Measurement of AFP and b-hCG in serum and CSF is routine in the preoperative

workup. If b-hCG or AFP levels are elevated, malignant germ cell elements are present even

if histologic examination gives a benign impression, because a small island of these cells

in a large tumor may be overlooked. Despite improved imaging and CSF markers, a definite

histologic diagnosis cannot be made without pathologic examination of tumor tissue.

SURGERY

Because of the wide variety of pineal region tumor subtypes, a histologic diagnosis is

mandatory for optimal patient management. The pineal region may be approached surgically

from one of several variations, above or below the tentorium. Nearly one-third of pineal

tumors are benign and curable with surgery alone. With malignant tumors, aggressive tumor

resection provides the best opportunity for accurate histologic diagnosis and may increase

the effectiveness of adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy. The overall operative

mortality is about 4%, with an additional 3% permanent major morbidity. The most serious

complication of surgery is hemorrhage into a partially resected malignant tumor. The most

common postoperative complications are ocular palsies, altered mental status, and ataxia;

all are usually transient. For patients with obviously disseminated tumor or those with

medical problems that pose excessive surgical risks, stereotactic biopsy is a reasonable

alternative for obtaining diagnostic tissue. Although gaining in popularity, stereotactic

biopsy is not performed routinely for these reasons: increased sampling error through

insufficient tissue analysis, increased risk of hemorrhage from adjacent deep venous

system and highly vascular pineal tumors, and the better prognosis that follows aggressive

resection.

POSTOPERATIVE STAGING

All patients with pineal cell tumors, malignant GCTs, and ependymomas are thoroughly

evaluated for CSF seeding even though this is a rare occurrence . High-resolution MRI is

more sensitive than computed tomography myelography. CSF cytology is not reliable in

predicting seeding.

RADIATION THERAPY

Radiation therapy consists of 4,000 cGy to the whole brain with an additional 1,500 cGy to

the pineal region; it is recommended for all patients with malignant pineal region tumors.

Spinal radiation is not recommended unless there is radiographic documentation of spinal

seeding.

Radiosurgery for pineal tumors is promising, but experience

is limited. It could be most useful for malignant pineal cell tumors and other small

malignant tumors (less than 3 cm in diameter), particularly if combined with fractionated

radiation. It may also be helpful for tumors that recur after radiation therapy.

Germinomas historically have had an excellent response to external fractionated

radiotherapy, and radiosurgery seems unlikely to improve upon those results.

CHEMOTHERAPY

Chemotherapy has been of most benefit with nongerminomatous malignant GCTs. The most

commonly used regimens are combinations of cisplatin, vinblastine, and bleomycin or

cisplatin and VP-16 (etoposide), which are usually given before radiation therapy. The

results of chemotherapy alone may be comparable with those of radiation therapy for pure

germinomas. There has been a trend to reduce radiation dosage because of long-term

neurotoxicity by combining it with chemotherapy.

LONG-TERM OUTCOME

Generally, benign pineal tumors are curable with surgery alone. Among malignant tumors,

the prognosis depends on the tumor histology. Germinomas have a 75% to 80% 5-year survival

with combined surgery and radiotherapy. Patients with a nongerminomatous malignant GCT

rarely survive beyond 2 years, but this may improve with better chemotherapy. About

one-third of astrocytomas are cystic tumors and are cured by surgery alone. Solid

astrocytomas behave clinically like other brainstem gliomas and have a 67% 5-year survival

rate. Radiation therapy is usually recommended for these tumors, but any effect on

survival is difficult to evaluate. Among pineal cell tumors, a few are discrete,

histologically benign, and completely resectable. Most malignant pineal cell tumors,

however, are not resectable and have a 55% 5-year survival rate with surgery and

radiation.

|