|

Distal cT2N0 Rectal

Cancer: Is There an Alternative to Abdominoperineal Resection?

Ramesh Rengan, Bruce D. Minsky.

JCO Aug 1 2005: 4905–4912.

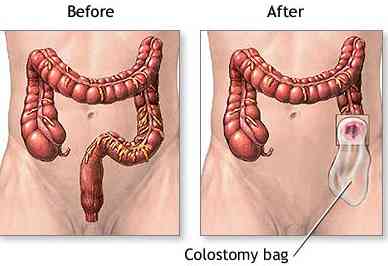

Patients with cT2N0 distal rectal cancer do

not require adjuvant therapy. However, when a patient refuses

an abdominoperineal resection (APR), is there an alternative?

The German CAO/ARO/AIO 94 preoperative versus postoperative

rectal trial reported that the incidence of sphincter

preservation in those patients who were judged clinically by

the operating surgeon to require an APR was significantly increased

in the preoperative (39%) versus postoperative arm (20%). Since

patients enrolled in that trial had either cT3, T4, and/or N+

disease, combined-modality therapy was necessary for adjuvant

therapy. In this report, we present the rates of sphincter

preservation and function, toxicity, local control, and

survival following preoperative pelvic radiation and selective

postoperative chemotherapy in patients with distal cT2N0 rectal

cancer who refused an APR.

The purpose of this trial is to

determine whether preoperative external-beam radiation therapy

can increase the rate of sphincter preservation for patients

with distal cT2N0 adenocarcinoma of the rectum. Between April

1988 and October 2003, 27 patients with distal rectal

adenocarcinoma staged T2 by clinical and/or endorectal

ultrasound who were judged by the operating surgeon to require

an APR were treated with

preoperative pelvic radiation alone

(50.4 Gy).

Surgery was performed 4 to 7 weeks later. If pathologic

positive pelvic nodes were identified, postoperative adjuvant

chemotherapy was recommended. The median follow-up was 55 months

(range, 9 to 140 months).

The pathologic complete response rate was 15% and

78% of patients

underwent a

sphincter-sparing procedure. The crude incidence of

local failure for patients undergoing a sphincter sparing

procedure was 10% and the 5-year actuarial incidence was 13%.

The actuarial 5-year survival for patients undergoing sphincter

preservation was as follows: disease-free, 77%; colostomy-free,

100%; and overall, 85%. Using the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer

Center sphincter function score, 54% of those undergoing a

sphincter-sparing procedure had good/excellent bowel function

at 12 to 24 months after surgery, and 77% had good/excellent

function at 24 to 36 months after surgery. Our data

suggest that for patients with cT2N0 distal rectal cancer who

require an APR, preoperative pelvic radiation improves

sphincter preservation without an apparent compromise in local

control or survival.

Whole

pelvic field. The lateral borders were 2.0 cm lateral to the

widest bony margin of the true pelvic side walls. The distal

border was at the base of the obturator foramen or 1 cm below

the anus, whichever was lower. The superior border was at the

L5/S1 junction. The posterior field margin was a minimum of 1

cm behind the anterior bony sacral margin, and blocks were used

to spare the posterior muscle and soft tissues. The external

iliac nodes were not included in the lateral radiation fields.

The anterior margin was at the most posterior aspect of the

symphysis pubis. The anus was considered part of the target

volume; therefore, it was included in the whole pelvic field.

The whole pelvis plus the primary nodal groups at risk received

46.8 Gy. This was followed by a 3.6-Gy boost to the primary

tumor bed.

Boost

field. The intent of the boost was to treat the primary tumor

with a 3-cm margin and not to include the nodal groups.

Therefore, the exact size was determined by the size and

location of the primary tumor. In general, field sizes measured

10 x 10 or 12 x 12 cm, and corner blocks were used if possible.

Opposed lateral fields were used. The boost dose was 3.6 Gy;

therefore, the total dose (pelvis + boost) was 50.4 Gy. |