|

|

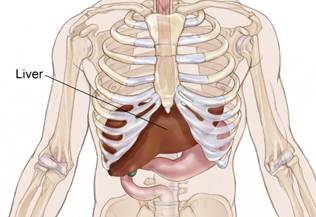

Nonsurgical therapies for localized hepatocellular carcinoma INTRODUCTION — Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is an aggressive tumor that frequently occurs in the setting of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. It is typically diagnosed late in the course of chronic liver disease, with the median survival following diagnosis of approximately 6 to 20 months. Although the mainstay of therapy is surgical resection, several other treatment modalities may also have a role. The patient's hepatic reserve often dictates therapeutic options

|

Treatment options are divided into surgical therapies (ie, resection, cryoablation, and orthotopic liver transplantation [OLT]), and nonsurgical therapies (ie, percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), systemic chemotherapy, and radiation). Here we will discuss the nonsurgical liver-directed treatment options for patients with localized HCC. Surgical treatment options for localized disease (including cryoablation), treatment of advanced disease, and the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of HCC are reviewed separately. (See appropriate topic reviews).

attempts to generate algorithmic approaches to the treatment of HCC are difficult since new treatments and indications for various treatments are evolving rapidly. Furthermore, therapeutic approaches tend to vary based upon the available expertise, as well as variability in the criteria for hepatic resection and orthotopic liver transplantation. These issues and a general approach to treatment of HCC are discussed in detail elsewhere.

PERCUTANEOUS ETHANOL INJECTION — Before the advent of RFA, PEI had been the most widely accepted, minimally invasive method for treating HCC. Although it is low cost, requires a minimal amount of equipment, and has good clinical results, the ease and efficacy of RFA has supplanted its use in many areas (see below).

Injection of 95 percent ethanol into a tumor can induce tumor necrosis and shrinkage, and may also improve survival. The mechanism of action is cytoplasmic dehydration with subsequent coagulation necrosis and a fibrous reaction. Ethanol also affects endothelial cells and causes platelet aggregation, which leads to thrombosis of tumor microvasculature and tissue ischemia.

Patient selection — PEI is often considered for patients with small HCCs who are not candidates for resection due to their poor functional hepatic reserve. Local recurrence is common in tumors >5 cm in diameter; as a result, PEI is generally not recommended for large tumors . However, local recurrence rates as high as 38 percent have been reported for tumors up to 3 cm in diameter. Because of these high recurrence rates, pain associated with application, and need for multiple treatments, we typically consider PEI only in patients with solitary tumors <2 cm in diameter who do not have the hepatic reserve to withstand resection. Lesions in the dome of the liver should not be considered for this approach.

PEI may also be indicated in noncirrhotic patients with small tumors that cannot be resected for technical reasons. The use of this modality to treat patients with small HCCs who are awaiting OLT has not been well studied; however, this seems to be a reasonable choice in those faced with a long waiting period.

Contraindications — Candidates for PEI must have tumors whose volume is less than 30 percent of the total liver volume. It is contraindicated in patients with extrahepatic disease, portal vein thrombosis, Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis with a prothrombin time >40 percent of normal, or a platelet count below 40,000/µl

Technique — For smaller lesions, PEI can be performed as an outpatient, with multiple separate injection sessions (eg, twice weekly injection of 1 to 8 mL ethanol for a total of 4 to 12 sessions). Alternatively, an inpatient "one shot" technique with the patient under general anesthesia may be employed, in which approximately 60 to 150 mL of ethanol is delivered via multiple injections over 30 minutes

Following treatment, patients can be monitored with ultrasound (US) or CT scans to determine if additional therapy is necessary. Most patients require multiple injections. However, at least in one series, a four-year survival rate of 44 percent was reported with single session injection therapy, even in patients with large tumors

Results — For HCC <5 cm

in diameter, the complete ablation rate is 70 to 75 percent, while for tumors 5 to 8 cm in

diameter, the ablation rate is lower, approximately 60 percent. However, as noted above,

the local recurrence rates for tumors >3 cm is high, limiting the utility of PEI for

larger tumors. Estimate one-, three-, and five-year survival rates for patients with

Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis and a single HCC ![]() 5 cm are 98, 79, and 47 percent,

respectively]. In contrast, patients with solitary lesions 5 to 10 cm in diameter had one-

and three-year survival rates of 73 and 42 percent, respectively. The three-year survival

rate among patients with multiple tumors was 31 percent in one series

5 cm are 98, 79, and 47 percent,

respectively]. In contrast, patients with solitary lesions 5 to 10 cm in diameter had one-

and three-year survival rates of 73 and 42 percent, respectively. The three-year survival

rate among patients with multiple tumors was 31 percent in one series

Not surprisingly, long-term results are somewhat worse in patients with greater underlying liver dysfunction. As an example, in a series of 112 patients, the one-, three-, and five-year survival rates for patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis were 96, 72, and 51 percent, respectively, while those with Child-Pugh class B cirrhosis had a 94 and 25 percent one- and three-year survival rate, respectively, with no patients surviving five years or longer

PEI plus interferon —

Following PEI, the majority of recurrences occur at different sites within the liver. In

view of the beneficial effect of interferon (IFN) therapy in patients with chronic

hepatitis C (HCV), the impact of "adjuvant" IFN in patients with HCC and HCV was

evaluated in a trial that randomly assigned 74 patients with compensated cirrhosis, three

or fewer HCC nodules, and a low hepatitis C virus RNA load (![]() 2 x 10(6)

copies/mL) to IFN (6 MU three times weekly for 48 weeks) or observation following complete

ablation by PEI Although the rate of first recurrence of new foci was similar, the rate of

subsequent recurrences appeared lower, and survival was better in the group receiving

interferon (five- and seven-year survival rates of 68 versus 48 percent and 53 versus 23

percent, respectively). Although a similar degree of benefit was suggested in a subsequent

Chinese trial involving 30 patients, the role of interferon in this setting remains

unclear.

2 x 10(6)

copies/mL) to IFN (6 MU three times weekly for 48 weeks) or observation following complete

ablation by PEI Although the rate of first recurrence of new foci was similar, the rate of

subsequent recurrences appeared lower, and survival was better in the group receiving

interferon (five- and seven-year survival rates of 68 versus 48 percent and 53 versus 23

percent, respectively). Although a similar degree of benefit was suggested in a subsequent

Chinese trial involving 30 patients, the role of interferon in this setting remains

unclear.

Adverse effects — PEI is generally well tolerated; however, side effects such as localized pain due to the necrosis and generalized peritoneal irritation due to ethanol leakage are common, and may reduce patient compliance. Serious complications such as intraperitoneal hemorrhage, hepatic insufficiency, bile duct necrosis or biliary fistula, hepatic infarction, hypotension, or renal failure are rare, occurring in less than 5 percent of patients

PEI versus surgery — For patients with small tumors, PEI may produce survival rates similar to surgical resection. In one study, for example, survival following resection or PEI was evaluated in 63 patients who had a solitary HCC less than 4 cm. Although tumor recurrence rates at two years were lower in the surgical group (45 versus 66 percent), these differences were only significant for cases with tumors between 3 and 4 cm. Overall survival at one, two, three, and four years were similar in the groups (81, 73, 44, and 44 percent versus 83, 66, 55, and 34 percent, respectively) even though the patients treated with PEI had more advanced liver disease prior to treatment. Similar results have been achieved with the percutaneous injection of acetic acid, which may have fewer side effects than ethanol

PEI plus other local therapies — In patients with small HCCs, the combination of PEI and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) may provide better local control than PEI alone. In one trial, 52 patients with one to three HCCs measuring <3 cm were randomly assigned to PEI alone or preceded by one course of TACE (using lipiodol plus epirubicin and Gelfoam). The cumulative detection rates for residual disease were significantly lower at one and three years with TACE-PEI (3.7 and 19.3 percent, respectively) compared to PEI alone (34.2 and 39.3 percent, respectively). Nevertheless, the cumulative survival rates at one, three, and five years were not significantly different (100, 81, and 40 percent for TACE-PEI, and 91, 66, and 38 percent for PEI alone, respectively).

RADIOFREQUENCY ABLATION — An additional method of treating HCCs involves the local application of radiofrequency thermal energy to the lesion, in which a high frequency alternating current moves from the tip of an electrode into the tissue surrounding that electrode. As the ions within the tissue attempt to follow the change in the direction of the alternating current, their movement results in frictional heating of the tissue. As the temperature within the tissue becomes elevated beyond 60ºC, cells begin to die, resulting in a region of necrosis surrounding the electrode

Patient selection — RFA has been used in patients who do not meet resectability criteria for HCC, and yet are candidates for a liver-directed procedure based upon the presence of liver-only disease. Some clinicians restrict RFA to cirrhotic patients of Child-Pugh class A or B severity only. Although there is no absolute tumor size beyond which RFA should not be considered, the best outcomes are in patients with a single tumor size <4 cm. Percutaneous RFA is also an effective means of treating recurrent HCC in the liver following partial hepatectomy

Some operators have been reluctant to perform RFA in patients with subcapsular tumors,

since needle-track seeding was observed in 4 of 32 patients in one series, all of whom had

tumors ![]() 1 cm

from the hepatic capsule. However, a cooled tip electrode was used in these patients,

which may have permitted viable tumor cells to survive the procedure. One of the authors

(SC) has not observed any case of needle track seeding in over 200 patients with HCC

treated with a standard RFA electrode. RFA may sometimes be avoided for treatment of

lesions that are located in the dome or along the inferior liver edge for fear of

diaphragmatic or intestinal perforation. However, with attention to technique (such as

insulating adjacent bowel from the thermal process), these lesions can be successfully

treated Tumors at the inferior edge of the liver should not be treated percutaneously (and

instead by a laparoscopic or open approach) if the stomach, duodenum, or transverse colon

lies in close proximity to the tumor.

1 cm

from the hepatic capsule. However, a cooled tip electrode was used in these patients,

which may have permitted viable tumor cells to survive the procedure. One of the authors

(SC) has not observed any case of needle track seeding in over 200 patients with HCC

treated with a standard RFA electrode. RFA may sometimes be avoided for treatment of

lesions that are located in the dome or along the inferior liver edge for fear of

diaphragmatic or intestinal perforation. However, with attention to technique (such as

insulating adjacent bowel from the thermal process), these lesions can be successfully

treated Tumors at the inferior edge of the liver should not be treated percutaneously (and

instead by a laparoscopic or open approach) if the stomach, duodenum, or transverse colon

lies in close proximity to the tumor.

Technique — A needle electrode is advanced into the tumor via a percutaneous, laparoscopic, or open (laparotomy) route. The needle electrode we have used most frequently is a 14-gauge, 15 to 25 cm long, insulated cannula containing 10 individual hook-shaped electrode arms or tines. Upon deployment, the array of tines extends out to a diameter of either 2.0, 3.0, 3.5, or 4.0 cm. Tumors less than 3 cm in their greatest diameter can be ablated with the placement of a needle electrode with an array diameter of 3.5 cm when the electrode is positioned in the center of the tumor.

Using US to guide placement, the needle electrode is advanced into the area of the tumor to be treated. Once the tines have been extended or deployed into the tissue, the needle electrode is attached to a radiofrequency generator and treatment is performed.

Tumors >3 cm require more than one deployment of the needle electrode. Typically, the array is first placed at the most posterior interface between the tumor and nonmalignant liver parenchyma, and then repositioned for repeat deployments anteriorly at 2.0 to 2.5 cm intervals within the tissue. In order to mimic a surgical margin in these unresectable tumors, the needle electrode is used to produce a thermal lesion that incorporates not only the tumor but also nondiseased liver parenchyma in a zone 1 cm wide surrounding the tumor.

Results — As with PEI, patients can be monitored by US or CT. In the subset of patients with an elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level prior to RFA, this marker can be useful to detect both persistent or recurrent disease. In one series, recurrence developed in over 90 percent of patients whose serum AFP did not return to normal following RFA. Unfortunately, serum AFP levels are normal in 40 percent of patients with HCC <2 cm in diameter, and in 28 percent of those with tumors 2 to 5 cm in diameter.

The vast majority of reports are limited to follow-up of 20 months or less, which compromises assessment of long-term outcomes. Local recurrence rates range from 0 to 28 percent, but average 5 to 6 percent. Three of the largest series with longest follow-up are described in detail:

- In one report, 149 tumor nodules in 110 patients with HCC and cirrhosis (Child class A, B, or C in 45, 28, and 18 percent, respectively) were treated with RFA (median tumor size treated percutaneously or intraoperatively, 2.8 and 4.6 cm, respectively. With a median follow-up of 19 months, 96 percent of patients were controlled locally; all four recurrences developed within six months at the periphery of tumors that were >4 cm. At last follow-up, 47 percent had no evidence of intrahepatic or extrahepatic recurrence. Fourteen patients (13 percent) developed complications, including ascites, hydropneumothorax, pleural effusion, fever, abdominal pain, bleeding, transient jaundice, and in one patient, transient ventricular fibrillation

- A second series included 319 patients who underwent RFA as primary treatment for HCC and cirrhosis (Child class A, B, or C in 69, 30, and 1 percent, respectively) With a median follow-up of 2.3 years, the Kaplan-Meier estimates for cumulative survival at 1, 2, 3, and 5 years were 95, 86, 78, and 54 percent, respectively. Cumulative survival rates 1, 2, 3, and 5 years in an additional 345 patients who underwent RFA for locally recurrent tumor were 92, 76, 62, and 38 percent, respectively. In the combined population, local control was achieved in 97 percent.

- The impact of the initial RFA response to long-term outcomes was studied in a report of 282 cirrhotic patients with early nonsurgical HCC who were treated with percutaneous ethanol injection and RFA over a 15 year period at the Barcelona clinic. An initial complete response was achieved in 192, 80 of whom were sustained. The overall 1, 3, and 5-year survival rates were 87, 51, and 27 percent, respectively. However, 42 percent of patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis who had an initial complete response were alive at five years; this figure increased to 63 percent with tumors 2 cm or smaller.

The utility of RFA for larger lesions is less certain. In one series of 114 patients

with 126 tumors >3 cm in diameter, complete necrosis was observed in 60 lesions (48

percent), while nearly complete necrosis was observed in an additional 40 lesions (32

percent). Two major complications (death, hemorrhage requiring laparotomy) and five minor

complications (self-limited hemorrhage, persistent pain) were observed. In the series

described above, the three-year survival rates for lesions >5 cm compared to those ![]() 2 cm or 2.1 to 5

cm were 59 versus 91 and 74 percent, respectively

2 cm or 2.1 to 5

cm were 59 versus 91 and 74 percent, respectively

Despite these data, it is difficult to reliably destroy tumors greater than 5 to 6 cm in diameter with current RFA devices. Newer equipment which can produce larger zones of ablation is currently under investigation. One small series suggests a possible benefit from adding a single dose of liposomal doxorubicin (20 mg IV) 24 hours prior to planned RFA. When five patients randomly assigned to receive doxorubicin were compared to five who underwent RFA only, the zone of coagulation necrosis at the RFA site was 3.4-fold larger. Clinical outcomes were not reported.

The benefit of RFA relative to surgical resection for patients with potentially resectable HCC remains controversial. Few retrospective series report long-term outcomes from RFA, and there are no randomized trials that directly compare the two treatments. Most clinicians consider that surgery is preferable, if it is feasible. Long-term survival rates of 40 percent or better can be achieved with limited hepatic resections for small tumors (<5 cm) in patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis. However, as noted above, selected patients may do as well with RFA.

Adverse effects — Although RFA is relatively well-tolerated, severe and potentially fatal complications can arise. In one report of 312 patients undergoing 350 procedures (226 percutaneous and the remainder intraoperative), five deaths were attributed to treatment (one each from liver failure, and colon perforation, three from portal vein thrombosis. Portal vein thrombosis was significantly more common in cirrhotic (2/5) compared to noncirrhotic livers (0/54) after intraoperative RFA performed during a Pringle maneuver. There were 37 nonfatal serious complications (incidence 11 percent), which included:

- Liver abscess in seven, which developed in all three patients with a bilioenteric anastomosis compared with less than 2 percent of the others

- Pleural effusion and skin burns in five patients each

- Hypoxemia during treatment in four patients

- Pneumothorax in three patients

- Subcapsular hematoma in two patients

- Acute renal insufficiency, hemoperitoneum, and needle tract seeding in one patient each

In addition, a self-limited postablation syndrome similar to that occurring after hepatic chemoembolization has been reported, with fever, malaise, chills, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, and elevated transaminase levels. Although not as well studied, the incidence seems to be lower after RFA than after chemoemboliation (36 percent in one report

RFA versus PEI — At least four prospective trials support the superiority of RFA over PEI The largest two trials are described in detail:

- In the largest trial, 232 consecutive patients with tumors

3 cm (the

majority Child-Pugh class A with HCV) were treated with either PEI or RFA. On average,

fewer treatment sessions were required for RFA (2.1 versus 6.4), and the incidence of

pain, fever, or serious adverse events was not different between the groups. With a median

follow-up of 3.1 years, patients treated with RFA had a 43 percent lower risk of overall

recurrence (four-year recurrence rate of 70 versus 85 percent), an 88 percent lower risk

of local tumor progression (1.7 versus 11 percent at four years), and better survival

(four-year overall survival 74 versus 57 percent).

3 cm (the

majority Child-Pugh class A with HCV) were treated with either PEI or RFA. On average,

fewer treatment sessions were required for RFA (2.1 versus 6.4), and the incidence of

pain, fever, or serious adverse events was not different between the groups. With a median

follow-up of 3.1 years, patients treated with RFA had a 43 percent lower risk of overall

recurrence (four-year recurrence rate of 70 versus 85 percent), an 88 percent lower risk

of local tumor progression (1.7 versus 11 percent at four years), and better survival

(four-year overall survival 74 versus 57 percent).

- Similar results were found in a Taiwanese trial of 157 patients with 186 HCCs

4 cm who were

randomly assigned to RFA or PEI (at two different doses). Compared to higher and standard

dose PEI, fewer sessions were required to achieve complete tumor necrosis with RFA, and

the RFA group had the lowest three-year local tumor progression rate (18 versus 33 and 45

percent, respectively), and the highest cancer-free survival rate (37 versus 20 and 17

percent, respectively).

4 cm who were

randomly assigned to RFA or PEI (at two different doses). Compared to higher and standard

dose PEI, fewer sessions were required to achieve complete tumor necrosis with RFA, and

the RFA group had the lowest three-year local tumor progression rate (18 versus 33 and 45

percent, respectively), and the highest cancer-free survival rate (37 versus 20 and 17

percent, respectively).

Summary — Although neither RFA nor PEI have been directly compared to supportive care alone, in our opinion, RFA is a safe and effective local treatment option, particularly for cirrhotic patients with small unresectable HCCs. It should be considered an effective technique to produce local control in the majority of HCC patients, with the possibility of effecting long-term, disease-free survival in selected patients. Compared to other local treatments (eg, cryoablation, PEI), RFA has proven to have the lowest number of side effects, while being efficacious and cost-effective. Nevertheless, in Europe, PEI continues to be preferred over RFA for most patients with small unresectable tumors.

LASER AND MICROWAVE THERMAL ABLATION — In addition to radiofrequency ablation, local thermal ablation may also be accomplished using alternative energy sources such as lasers or microwaves

Laser thermal ablation — In the largest series of 74 patients with small primary HCCs, a 5.0 watt laser was coupled to one to four fibers, directed percutaneously into the liver through a 21 gauge needle, and tumors treated for 6 to 12 minutes per session. There were no major complications during 117 sessions, and tumors required an average of 1.3 sessions. On follow-up CT scans at three months, 89 of 92 treated lesions were completely non-enhancing, suggesting complete necrosis. With a mean 25 month follow-up, local recurrence rates in the vicinity of the primary tumor were under 6 percent, while recurrence rates within other liver segments ranged from 24 to 73 percent; the two- and five-year survival rates were 68 and 15 percent, respectively.

Although these results seem promising, the benefits compared to other means of local tumor ablation are unclear. Furthermore, the equipment is expensive and not widely available.

Microwave hyperthermia —

The largest series reporting long-term outcomes involved 288 patients treated at a single

Chinese institution over an eight year period. The maximum tumor diameter ranged from 1.2

to 8 cm (mean 3.75), and 63 percent had a single lesion. With a mean follow-up of 31

months, only 24 patients (8 percent) had local regrowth of a lesion treated with microwave

hyperthermia, while 76 (26 percent) developed new tumors elsewhere. Cumulative survival

rates at 1,3, and 5 years were 93, 72, and 52 percent, respectively, and were

significantly better for patients with maximum tumor size ![]() 4 cm as compared to larger tumors. Not

surprisingly, the highest probability of long-term survival was observed in patients with

Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis who were treated for a single lesion, <4 cm in

diameter.

4 cm as compared to larger tumors. Not

surprisingly, the highest probability of long-term survival was observed in patients with

Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis who were treated for a single lesion, <4 cm in

diameter.

TRANSARTERIAL CHEMOEMBOLIZATION — The observation that the majority of the blood supply to HCCs is derived from the hepatic artery has led to the development of techniques designed to eliminate the tumor's blood supply or to administer cytotoxic chemotherapy directly to the tumor. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) involves the injection of a chemotherapeutic agent, with or without lipiodol or a procoagulant material, into the hepatic artery. Lipiodol is an oily contrast agent that promotes intratumoral retention of chemotherapy drugs. Simultaneous or sequential occlusion of the hepatic artery until stagnation of blood flow to the tumor occurs may result in greater antitumor efficacy than chemotherapy alone.

Technique and contraindications — TACE can generally be accomplished using a standard 4 to 5 F hydrophilic Cobra catheter and a wide variety of chemotherapeutic agents and embolic particles Neither the optimal chemotherapeutic agent nor the best embolization method (ie, gelatin sponge [Gelfoam], starch, glass microspheres, polyvinyl alcohol) has been established. Contraindications to this technique include:

- Absence of hepatopedal blood flow (portal vein thrombosis)

- Encephalopathy

- Biliary obstruction

Relative contraindications include a variety of other factors including, but not limited to:

- Serum bilirubin >2 mg/dL

- Lactate dehydrogenase >425 U/L

- Aspartate aminotransferase >100 U/L

- Tumor burden involving >50 percent of the liver

- Cardiac or renal insufficiency

- Ascites, recent variceal bleed, or significant thrombocytopenia

Indications — TACE has been used in three settings:

- Treatment of large unresectable HCC

- Prior to resection or radiofrequency ablation

- Prior to transplant

Its benefit in any of these settings depends upon patient characteristics. This was illustrated in a study that constructed a multivariate model predicting survival from a cohort of 143 patients who had been treated with TACE Pretreatment independent predictors of worse survival were the serum alpha fetoprotein concentration >400 U/L, tumor volume >50 percent of liver volume, and increasing Child-Pugh score. Posttreatment independent predictors of worse survival included the presence of portal vein thrombosis and diffuse heterogeneous uptake of Lipiodol on CT. Based upon the pretreatment variables, patients with the most favorable characteristics were more likely to be alive at 12 months compared to those with the least favorable characteristics (survival of approximately 70 versus 20 percent). These predictors likely represent indicators of advanced disease and poor hepatic functional reserve, and would likely portend to adverse outcomes irrespective of the intervention.

Primary treatment of large unresectable HCC — TACE with or without lipiodol is typically used in patients who have large (ie, >10 cm) HCCs that are not amenable to other treatments. Approximately 35 percent have an objective antitumor response. However, despite the widespread acceptance of this modality, and apparently prolonged survival in multiple phase II studies, three of five large randomized trials have failed to demonstrate a survival advantage. In the negative trials, TACE reduced tumor growth but was not associated with significantly improved survival compared to conservative management of patients with advanced HCC. Furthermore, in one study, TACE caused two deaths and was associated with signs of liver failure in 51 percent of treated patients . Comparison of these studies is difficult due to differences in chemoembolization techniques, patient selection, and the variable number of repeated treatments.

In contrast, two controlled trials have shown a survival advantage for TACE in selected patients with preserved liver function:

- In the first trial, only 80 of 279 Asian patients presenting with unresectable HCC

fulfilled the strict entry criteria (no variceal bleeding within the last three months,

serum bilirubin

5 mg/dL, serum albumin >2.8 g/L, prothrombin time <4 seconds over

control, no portal vein thrombosis), and were randomly assigned to symptomatic treatment

or to repetitive courses of intraarterial emulsified cisplatin, lipiodol, and gelatin

sponge particles. The actuarial survival was significantly higher in the treated group at

one, two, and three years (57, 31, and 26 percent, respectively) compared to controls (32,

11, and 3 percent, respectively). Although there were more cases of liver failure in the

treated group, the overall impact of TACE on survival was beneficial (relative risk of

death 0.49, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29-0.81), and liver function in the survivors

was not significantly different from the control group.

5 mg/dL, serum albumin >2.8 g/L, prothrombin time <4 seconds over

control, no portal vein thrombosis), and were randomly assigned to symptomatic treatment

or to repetitive courses of intraarterial emulsified cisplatin, lipiodol, and gelatin

sponge particles. The actuarial survival was significantly higher in the treated group at

one, two, and three years (57, 31, and 26 percent, respectively) compared to controls (32,

11, and 3 percent, respectively). Although there were more cases of liver failure in the

treated group, the overall impact of TACE on survival was beneficial (relative risk of

death 0.49, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29-0.81), and liver function in the survivors

was not significantly different from the control group.

- In the second report, only 112 of 903 assessed patients presenting with unresectable HCC

were eligible (Child-Pugh A/B, Okuda stage I/II , age <75, no active gastrointestinal

bleeding, platelet count

50,000/µl, serum bilirubin

50,000/µl, serum bilirubin  5 mg/dL, no portal obstruction) for

randomization between symptomatic treatment alone, arterial embolization with gelfoam, or

lipiodol chemoembolization with doxorubicin and gelfoam. In both treated groups, arterial

embolization was repeated two and six months later, and every six months thereafter. The

one and two year survival probabilities were significantly greater with chemoembolization

(82 and 63 percent) but not arterial embolization (75 and 50 percent) when compared to

control (63 and 27 percent).

5 mg/dL, no portal obstruction) for

randomization between symptomatic treatment alone, arterial embolization with gelfoam, or

lipiodol chemoembolization with doxorubicin and gelfoam. In both treated groups, arterial

embolization was repeated two and six months later, and every six months thereafter. The

one and two year survival probabilities were significantly greater with chemoembolization

(82 and 63 percent) but not arterial embolization (75 and 50 percent) when compared to

control (63 and 27 percent).

The importance of considering patient selection when interpreting the results of these studies cannot be overemphasized. In the latter trial, the survival rate in the control group (63 percent at one year) was significantly higher than that reported in most treatment studies for advanced HCC, in which the median survival is usually less than six months.

A meta-analysis that included seven randomized trials of arterial embolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma lends further support to the use of chemoembolization. Compared to control (either conservative management or suboptimal therapy [eg, intravenous 5-fluorouracil]), there was a statistically significant improvement in two-year survival with arterial embolization (odds ratio 0.53, 95% CI 0.32-0.89) that was evident for chemoembolization but not embolization alone. A second meta-analysis that was limited to four trials comparing TACE to supportive care only failed to demonstrate any survival benefit for this approach. However, given the importance of patient selection noted above, the value of meta-analysis as a tool to assess efficacy in HCC is limited.

TACE should be limited to the minimum number of procedures necessary to control the tumor. The benefit of multiple repeated cycles of TACE must be weighed against adverse effects of the procedure, particularly in those with borderline liver function. TACE causes some degree of ischemic hepatic damage, which has the potential to lead to decompensation. The incidence of decompensation as a complication of TACE is closely related to pretreatment hepatic function. Multiple courses of TACE, especially if they are spaced too closely together, may lead to more deaths from liver failure despite successful tumor shrinkage. This was illustrated in a retrospective report describing the use of TACE prior to planned resection of HCC [60]. While successful in postponing death from tumor at 1.5 years, the use of TACE led to a worse survival in cirrhotics at four years (35 versus 72 percent). Thus, excess deaths from deterioration of liver function may balance out any prolongation of survival that results from enhanced tumor control.

Prior to resection or ablation — A number of uncontrolled series and at least one controlled trial have suggested that TACE used prior to an attempt at resection is associated with increased mortality. This topic is discussed in detail elsewhere. Other groups use TACE prior to radiofrequency ablation of larger tumors in patients who are not candidates for resection or transplantation.

Prior to OLT — Several small series have demonstrated the feasibility of TACE prior to OLT. Despite its uncertain benefit, it remains a common method in many transplant centers both to limit the amount of viable tumor at the time of transplantation, and to help bridge the often prolonged waiting period while a patient is listed. This topic is discussed in detail elsewhere.

Complications — TACE is frequently complicated by pain, fever, nausea, fatigue, and elevated transaminases, commonly referred to as the postembolization syndrome. These symptoms are usually self-limited, and their presence does not correlate with a more favorable outcome. In one prospective study of 197 sessions of TACE performed in 59 patients with HCC, fever, abdominal pain, and nausea or emesis complicated 74, 45, and 59 percent of procedures. Acute hepatic decompensation developed after 39 sessions (20 percent), and was irreversible in six (3 percent). Patients with irreversible changes were significantly more likely to have higher pre-TACE bilirubin levels, more prolonged prothrombin time, and more advanced cirrhosis. Uncommon problems following TACE include ischemic cholecystitis, hypothyroidism, or the development of a pleural effusion.

Recommendation — Based upon these data, we do not routinely offer TACE to all patients, but reserve it for symptomatic patients with unresectable HCC, in whom the tumor is either too large or multifocal for RFA. Patients must have a patent portal vein, good performance status, and preserved hepatic function. We use doxorubicin alone at a fixed dose for the procedure, although other centers add other drugs such as mitomycin and cisplatin; there is no evidence that either approach is better. Lipiodol is always used in an effort to enhance embolization of the smaller vessels and thus retention of the chemotherapy (again in the absence of definitive data). We do not routinely recommend TACE in patients with HCC prior to planned resection and its efficacy prior to OLT is uncertain.

In general, we wait one month in between procedures if both the right and left lobes require treatment. We only repeat the procedure if there is evidence that the tumor is growing.

RADIOTHERAPY — HCC is a radiosensitive tumor, but it is located in an extremely radiosensitive organ. The major drawbacks with RT are the poor radiation tolerance or normal liver, and difficulty with tumor localization.

External beam RT — Limited experience with local photon or proton beam RT for unresectable HCC suggests that it is tolerable and induces a substantial tumor response. One report, for example, included 24 patients who were treated with local external beam RT (mean tumor dose 52 Gy in daily 1.8 Gy fractions) after failing TACE. An objective response was observed in 16 (67 percent) including one complete response. Survival rates at one, two, and three years were 85, 58, and 33 percent, respectively. The median survival was 14 months after starting RT. Toxicity included transient abnormal liver function tests (n =13), thrombocytopenia (n = 2), gastroduodenal ulcer (n= 3), and duodenitis (n = 2).

With the development of three dimensional conformal radiation (3D-CRT) techniques, RT can be more safely delivered to the tumor-bearing parts of the liver with less liver toxicity. Investigators from Michigan have combined conformal RT with concurrent intrahepatic artery floxuridine for intrahepatic malignancies, including HCC. Of the 128 patients enrolled in their latest study, 35 had unresectable HCC. The median delivered RT dose was 60.75 Gy. Objective responses were complete in 1, partial in 13, stable disease in 11, and unevaluable in 10. Median survival was 15.2 months.

Still, one of the problems with focal RT is the high intrahepatic recurrence rate (64 percent in the conformal RT plus intrahepatic artery floxuridine series described above. Several studies suggest favorable long-term results when local external beam RT is combined with TACE

- One prospective trial, 30 patients with unresectable HCCs (mean 9 cm in size) received TACE followed by RT The partial response rate was 63 percent, median survival 17 months, and survival rates at two and three years were 33 and 22 percent, respectively. It is unclear if these results are better than could have been achieved with TACE alone.

- This approach may be particularly beneficial for patients with portal vein thrombosis. In one series of 19 patients with unresectable HCC complicated by thrombus in the first branch of the portal vein, focal 3D-CRT was combined with TACE (Lipiodol, epirubicin, mitomycin, and gelatin sponge cubes) Eleven patients had an objective response (58 percent), and eight (41 percent) were still alive at one year.

Although these results are encouraging, the place of RT among other treatment options for patients with unresectable HCC has yet to be defined. It may be a reasonable option in patients who have failed other local modalities, have no extrahepatic disease, limited tumor burden, and relatively good liver function. Technologic developments in delivering more precisely targeted RT (ie, intensity-modulated and image-guided approaches and stereotactic radiotherapy) and proton beam radiotherapy may improve the benefit/toxicity ratio, and have an impact on future therapy

Selective internal radiation with radioactive isotopes — As noted previously, external beam RT for treatment of intrahepatic malignancies is limited by low tolerance of normal tissues. An alternative means of delivering focal radiation employs radioactive isotopes (eg, iodine-131 [131I]- labeled lipiodol or yttrium-90 [90Y]-tagged glass microspheres) that are delivered selectively to the tumor via the hepatic artery. Few reports have studied 131l-labeled lipiodol in locally unresectable disease, although data in the adjuvant setting are promising. . The use of this agent is limited by its lack of availability, at least in the United States.

Early reports suggest that radioembolization using intrahepatic artery administration of (90Y)-tagged glass microspheres is safe, and induces objective responses in patients with unresectable HCC In a report of the largest series of 80 patients with advanced unresectable but nonmetastatic HCC, 65 had been followed for at least one year. There were 18 partial and 24 minor responses, and 19 had stable disease for prolonged periods. However, 80 percent had a major decrease in tumor vascularity on CT. The main clinical toxicities were episodic nausea, abdominal pain, fatigue, and transient hyperbilirubinemia. Median survival durations stratified by hepatic functional status were

- Okuda I versus II — 628 versus 281 days, respectively

- Child-Pugh A versus B — 567 versus 245 days

- CLIP 0,1-2, or >2 — 812, 452, and 216 days

Longer-term follow-up of these studies, and additional experience is needed with this technique. Ultimately, randomized controlled trials will be needed to compare its efficacy with other nonsurgical therapies. This approach is also being applied to hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer.

PERCUTANEOUS CISPLATIN/EPINEPHRINE GEL — A relatively new drug delivery system for local tumor ablation is a cisplatin-epinephrine injectable gel which provides a sustained high intratumoral cisplatin concentration. The efficacy of this approach was illustrated in a report of 58 previously untreated patients with unresectable HCC who received up to eight intratumoral injections of between 1 and 10 mL (with dose based upon tumor volume) administered weekly The overall and complete response rates were 53 and 28 percent, respectively, and no completely responding lesion progressed after treatment. Treatment was complicated by fever in 47 percent, and mild to moderate asthenia, vomiting, or chills in approximately 20 percent of cases each.