|

Hereditary or Familial Colon Cancer |

|

|

Hereditary or Familial Colon Cancer |

|

|

Colorectal cancer is a commonly diagnosed cancer in both men and women. Two kinds of observations indicate a genetic contribution to colorectal cancer risk: (1) increased incidence of colorectal cancer among persons with a family history of colorectal cancer; and (2) families in which multiple family members are affected with colorectal cancer, in a pattern indicating autosomal dominant inheritance of cancer susceptibility. |

| About 75% of patients with colorectal cancer have sporadic disease, with no apparent evidence of having inherited the disorder. The remaining 25% of patients have a family history of colorectal cancer that suggests a genetic contribution, common exposures among family members, or a combination of both. Genetic mutations have been identified as the cause of inherited cancer risk in some colon cancer-prone families; these mutations are estimated to account for only 5% to 6% of colorectal cancer cases overall. It is likely that other undiscovered major genes and background genetic factors contribute to the development of colorectal cancer, in conjunction with nongenetic risk factors. |

| The subject is so complicated, (see flow chart) that patients with a familial from should be managed by experts and genetic counselors. Some of the best web sites that discuss this subject: |

A detailed family history, including ethnicity, as well as a detailed medical and surgical history and physical examination, are paramount in screening for inherited colorectal cancer syndromes.

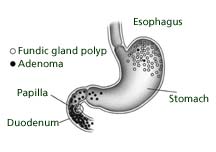

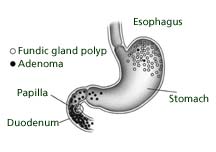

The history should include questions about colon cancer syndromes or syndrome-specific features such as, juvenile polyposis, Muir-Torre, Turcot, Peutz-Jeghers, and Cowden. A directed examination for extracolonic manifestations should include an eye examination, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, skin and soft tissue examination, and a thyroid examination. Certain physical features that may be helpful in the presymptomatic recognition of FAP include congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE), osteomas, odontomas, supernumerary teeth, epidermoid cysts, desmoids, and duodenal and other small-bowel adenomas. Presence of the duodenal and gastric cancers is also considered in FAP diagnosis. Additional screening measures include determining if the patient is positive for APC mutations or the likelihood of the patient's autosomal dominant inheritance Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal syndrome is autosomal dominant and comprises between 1%-5% of all cases of colorectal cancer. Mutation in mismatch repair (MMR) genes is the high risk factor for development of colorectal, endometrial, and ovarian cancer. Genetic testing for HNPCC is somewhat more complicated than testing for FAP because several different genes contribute to the development of HNPCC. A screening test that examines tumors for microsatellite instability (an imperfect, but helpful, molecular "fingerprint" of HNPCC) is often useful in guiding choices about whether further genetic testing is needed. Due to the high risk for colorectal cancer, intensive screening is essential, though the exact interval has not been fully established in clinical trials. The recommendations in this area are based on the best evidence available to date, but more data are still needed. Clinical clues that can alert a physician to the presence of HNPCC in a patient include: 1) colon cancer in a first- or second-degree family member; 2) colon cancer diagnosed under the age of 50 years; 3) multiple generations affected; 4) multiple primary cancers, including endometrial, ureteral/renal pelvis, small bowel, and stomach cancers; 5) the predominance of right-sided colon cancer; and 6) ovarian cancer. Breast cancer is not included in the guidelines as a risk factor and remains a fairly controversial aspect of what constitutes the clinical phenotype of HNPCC.