Because of the poor outcomes of surgery for gastric cancer, there has been much interest in adjunctive therapies that, when used in addition to surgical removal of the primary tumor, may improve survival. Adjuvant cytotoxic chemotherapy is successful in other gastrointestinal cancers, and many phase 3 clinical trials have explored this approach in gastric cancer. However, the survival benefit gained from the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in gastric adenocarcinoma is not clinically significant, and for this reason adjuvant chemotherapy has not become part of the standard of care in gastric cancer.

Nevertheless, there are other strategies in which cytotoxic chemotherapy may be beneficial. In this issue of the Journal, Cunningham and colleagues present the results of a phase 3 trial in which they evaluated the role of perioperative chemotherapy in the management of resectable gastric cancer. In this trial, patients with resectable gastric cancer were randomly assigned to a combination of chemotherapy and gastric resection or to gastric resection alone. The patients in the chemotherapy group were assigned to receive both preoperative and postoperative therapy with a regimen of three drugs — epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil (ECF). Patients in the surgery-only group underwent gastrectomy with curative intent and received no adjuvant therapy. The major outcomes were progression-free and overall survival. The trial enrolled 503 patients; 250 received perioperative chemotherapy and 253 were treated with surgical resection alone.

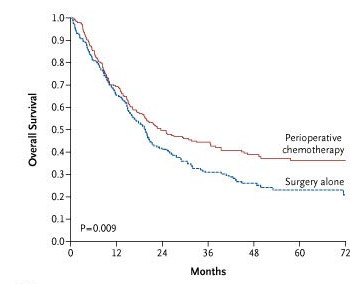

Analysis of the results of the trial convincingly demonstrated a benefit from the use of the ECF regimen. Five-year overall survival was 36 percent in the perioperative-chemotherapy group and 23 percent in the surgery-only group (P=0.008 by the log-rank test). This improvement in survival of 13 percentage points corresponds to a 25 percent relative reduction in the risk of death. Progression-free survival also was improved by chemotherapy. In the perioperative-chemotherapy group, other outcomes also showed encouraging trends, such as decreased tumor size and reduction in the extent of nodal metastases.

Whenever chemotherapy is used, it is important to assess drug toxicity. Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, for example, are clinically significant complications in patients who are about to undergo a major abdominal operation. Cunningham et al. found that perioperative chemotherapy was associated with acceptable rates of adverse events. Excluding patients with neutropenia (23 percent), less than 12 percent of patients had serious (grade 3 or 4) toxic effects. Although 15 of 237 patients (6 percent) discontinued treatment, mainly because of toxic effects, most patients were safely treated with chemotherapy followed by gastrectomy.

If perioperative chemotherapy with a regimen of ECF improves survival, causes tumor down-staging, and is safe, should it be considered a standard of care in the management of resectable gastric cancer? There are subtle aspects to this question and its answers. Cunningham and colleagues note that the ECF regimen was developed in the late 1980s and that there are now newer and less complex chemotherapy regimens with activity against advanced gastric cancer.12 Are these more recently developed treatments better than the ECF regimen? Clinical trials will provide the answer, and there is no doubt that newer regimens will be tested in trials of perioperative chemotherapy similar to the trial of Cunningham et al.

Undoubtedly, oncologists will debate the most appropriate chemotherapy regimen for gastric cancer, but more important is whether any sort of perioperative chemotherapy is the best way to improve the cure rate in resectable gastric adenocarcinoma. Part of the answer hinges on when clinicians first see patients with resectable gastric cancer. Perioperative chemotherapy may be a reasonable form of treatment for patients who are seen before gastrectomy, but patients who have already undergone gastric resection are obviously not candidates for this treatment. It is not unusual for patients with gastric cancer to be referred to an oncologist only after a gastrectomy with curative intent has been performed. Is there a standard of care for these patients?

A large phase 3 trial of postoperative therapy strongly suggested a benefit from the combination of irradiation and chemotherapy after gastrectomy. This trial, Intergroup Study 0116 (INT 0116), enrolled more than 550 patients who were randomly assigned to surgery alone or surgery followed by chemoradiation (fluorouracil and leucovorin plus external-beam radiation delivered to the site of the gastric resection and the areas of draining lymph nodes). These patients were at a clinically significant risk for relapse after gastric resection — 85 percent had lymph-node metastases and 65 percent had stage T3 or T4 tumors. Median survival in the surgery-only and chemoradiation groups was 27 and 36 months, respectively (P=0.005 by the log-rank test); the corresponding figures for disease-free survival were 19 and 30 months (P<0.001). One result of this trial was that postoperative chemoradiation was accepted as a standard of care among patients with resected gastric adenocarcinoma.

The most important question for physicians who treat patients with gastric cancer is whether the report by Cunningham et al. should influence their management of the disease. Is perioperative chemotherapy an advance in the treatment of gastric cancer? The trial conducted by Cunningham and colleagues was well designed and well executed, and clinicians can have confidence in the solid evidence that perioperative therapy with a regimen of ECF improves the outcome for patients with resectable gastric cancer identified before gastrectomy. The results of the study by Cunningham and colleagues provide a new option for the treatment of localized, resectable gastric cancer.

Background A regimen of epirubicin, cisplatin, and infused fluorouracil (ECF) improves survival among patients with incurable locally advanced or metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma. We assessed whether the addition of a perioperative regimen of ECF to surgery improves outcomes among patients with potentially curable gastric cancer.

Methods We randomly assigned patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the stomach, esophagogastric junction, or lower esophagus to either perioperative chemotherapy and surgery (250 patients) or surgery alone (253 patients). Chemotherapy consisted of three preoperative and three postoperative cycles of intravenous epirubicin (50 mg per square meter of body-surface area) and cisplatin (60 mg per square meter) on day 1, and a continuous intravenous infusion of fluorouracil (200 mg per square meter per day) for 21 days. The primary end point was overall survival.

Results ECF-related adverse effects were similar to those previously reported among patients with advanced gastric cancer. Rates of postoperative complications were similar in the perioperative-chemotherapy group and the surgery group (46 percent and 45 percent, respectively), as were the numbers of deaths within 30 days after surgery. The resected tumors were significantly smaller and less advanced in the perioperative-chemotherapy group. With a median follow-up of four years, 149 patients in the perioperative-chemotherapy group and 170 in the surgery group had died. As compared with the surgery group, the perioperative-chemotherapy group had a higher likelihood of overall survival (hazard ratio for death, 0.75; five-year survival rate, 36 percent vs. 23 percent) and of progression-free survival (hazard ratio for progression, 0.66).

Conclusions In patients with operable gastric or lower esophageal adenocarcinomas, a perioperative regimen of ECF decreased tumor size and stage and significantly improved progression-free and overall survival.