INTRODUCTION Craniopharyngiomas are rare, usually suprasellar, solid or mixed solid-cystic benign tumors that arise from remnants of Rathke's pouch along a line from the nasopharynx to the diencephalon. They are also known as Rathke pouch tumors, hypophyseal duct tumors, or adamantinomas. Craniopharyngiomas account for 1 to 3 percent of intracranial tumors, with an incidence of approximately 0.5 to 2 cases per million population per year . They are the third most common intracranial tumor in children, after gliomas and medulloblastomas, and account for up to 10 percent of intracranial tumors. There is a bimodal distribution in peak incidence rates.

PATHOLOGY Craniopharyngiomas are dysontogenetic tumors. They presumably arise from embryonic remnants of Rathke's pouch and grow slowly from birth. However, one case report documented the de novo development of a macroscopic craniopharyngioma two years after a normal magnetic resonance imaging study in a 55-year-old woman . Three basic histologic subtypes of craniopharyngioma have been described :

The tumors vary in size from small, solid, well-circumscribed masses to huge multilocular cysts that invade the sella turcica and displace neighboring cerebral structures. The majority of craniopharyngiomas consist of a single large cyst or multiple cysts that are filled with a turbid fluid containing cholesterol crystals. Craniopharyngiomas usually arise in the pituitary stalk in the suprasellar region adjacent to the optic chiasm. A small percentage arise within the sella , and a few tumors have been described within the optic system or the third ventricle . Tumor extension occurs in variable directions along the path of least resistance. The tumor may therefore extend into the basal cisterns or the base of the brain or displace the third ventricle superiorly . CLINICAL PRESENTATION Patients with craniopharyngiomas commonly present with pituitary hypofunction, visual difficulties, and severe headaches . The type of presentation varies in part with age.

Craniopharyngiomas can also cause more generalized symptoms, such as depression, independent of any hormone deficiency . The presumed cause is extension of tumor into the frontal lobes, striocapsulothalamic areas, or limbic system. These tumors invade the third ventricle more often than pituitary adenomas, sometimes causing obstruction to flow of spinal fluid and increased intracranial pressure with corresponding symptoms and signs. (See "Evaluation and management of elevated intracranial pressure in adults"). DIAGNOSIS Preoperatively, the diagnosis of craniopharyngiomas is usually suggested from computed tomographic (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. Craniopharyngiomas must be distinguished from other tumors in the parasellar area, including meningiomas, optic gliomas, teratomas, systemic histiocytosis, metastases, and infiltrative disorders such as sarcoidosis. Calcification in the suprasellar region is seen in about 80 percent of patients with craniopharyngioma and at least one cyst in 75 percent. Thus, a cystic calcified parasellar lesion is very likely to be a craniopharyngioma. MR imaging of the sellar region, including at least one contrast�enhanced sequence, should be sufficient in most instances to establish a preoperative diagnosis. Calcifications can also be seen on plain skull radiographs The distinction between craniopharyngioma and other tumors may be difficult both on clinical and radiographic grounds. The radiographic difficulty arises from the absence of clear delineation between the tumor and optic chiasm. The presence of edema spreading along the optic tract may be an indicator of craniopharyngioma. In one series, this pattern of edema was seen in five of eight consecutive patients with craniopharyngioma but in none of 15 patients with large pituitary adenomas compressing the optic chiasm or none of six patients with meningiomas of the sellar region . It is also useful to distinguish nonneoplastic cystic lesions such as Rathke's cleft cyst and arachnoid cyst from craniopharyngioma, because the type and aggressiveness of treatment, recurrence rate, and prognosis of these lesions vary. In a study of 52 patients, short-term memory loss and calcifications on MR imaging were more suggestive of a craniopharyngioma than a Rathke's cleft cyst or arachnoid cyst . Since most patients with craniopharyngioma have at least partial hypopituitarism, endocrine testing, particularly of adrenal and thyroid function, is indicated before surgery. (See "Diagnosis of hypopituitarism" and see "Diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency"). A detailed ophthalmologic examination including visual field testing helps to determine whether there is compression of the optic pathways and establishes a presurgical baseline. In some patients, the onset of symptoms is late and no calcification is seen on radiologic testing. In these patients, the diagnosis can only be established histologically. TREATMENT Therapeutic options for patients with craniopharyngioma include surgery, radiotherapy, and the combination of the two. Radiotherapy alone is usually restricted to patients with very small tumors, while the optimum extent of surgery remains controversial. In addition, several methods can be used to treat symptoms associated with cyst enlargement. After attempting surgical excision, Cushing concluded that surgical mortality would remain unacceptable until the multilocular epithelial cysts could be destroyed or inactivated. Total surgical excision became possible after the development of microsurgical techniques , and with use of these techniques recovery of some visual function occurs in almost 90 percent of symptomatic patients and complete recovery in up to one-third . However, continued experience has dampened the enthusiasm for extensive surgery for the following reasons:

Thus, many surgeons have adopted a more conservative approach which combines less aggressive surgery with radiotherapy. Aggressive surgery Proponents of this approach recommend radical surgery aimed at total removal of the tumor as the initial therapy of choice . Although there is a significantly higher incidence of early morbidity and mortality, there may be a better chance of cure with less risk of tumor progression and loss of quality of life. In addition, this approach allows radiotherapy to be reserved for the treatment of recurrence. Some surgeons therefore advocate total tumor removal in all cases, and accept mortality rates of up to 20 percent. Others attempt complete removal but perform subtotal resection if operative findings suggest total removal would be hazardous. One center reviewed the efficacy of the latter approach in 148 patients undergoing initial surgery and 20 patients with recurrent tumor; 30 were children under the age of 16 years. The tumors were usually approached via a craniotomy but a transsphenoidal approach was used in 24 percent for resecting intrasellar tumors. Tumor removal was considered complete when the surgeon was convinced that this had been achieved, and postoperative MR imaging showed no evidence of residual tumor. Among the patients undergoing initial surgery, total removal was achieved in almost one-half, with a much higher frequency in those undergoing transsphenoidal surgery; subtotal or partial removal was achieved in 22 and 14 percent, respectively. In comparison, only 21 percent of recurrent tumors were completely removed. Factors which limited tumor removal included adherence of the tumor to the adjacent structures, calcification of more than 10 percent of the tumor mass and tumor size. Postoperative death occurred in one of the 148 patients undergoing primary surgery and 2 of the 20 patients operated on for recurrent tumor. The operative morbidity rate was 13 percent with primary transcranial surgery, 6 percent with primary transsphenoidal surgery, and 16 percent in surgery for recurrent disease. The 10-year actuarial survival rate was 93 percent. Recurrence after "complete" removal of tumor occurred in 11 percent of patients overall, but there were no recurrences in the patients treated with a transsphenoidal approach. The cumulative rate of recurrence-free survival was 87 percent at five years and 81 percent at 10 years. A much higher recurrence rate of about 50 percent occurred after partial tumor removal. In addition, nine of thirteen patients treated with partial removal had progression of disease. None of these patients received radiotherapy. The functional outcome varied with the type of procedure. With primary transcranial surgery, symptoms of chiasmal compression regressed completely in approximately one-third and partially in another one-third; visual deterioration occurred in 15 percent. At a mean follow-up of five years, 78 percent were living independently without impairment. With primary transsphenoidal surgery, symptoms of chiasmal compression regressed completely in 47 percent and partially in another 40 percent. There were no cases of visual deterioration. Post-op endocrine function Endocrine function was assessed preoperatively and at three months after surgery . Diabetes insipidus was the most common deficiency associated with surgery; the overall percentage of patients with diabetes insipidus increased from 16 to 66 percent and from 23 to 69 percent after transcranial and transsphenoidal surgery, respectively. Transcranial surgery was also associated with increases in the frequency of adrenal insufficiency (23 to 59 percent), hypothyroidism (19 to 38 percent), and panhypopituitarism (11 to 35 percent). In contrast, the rates of hypogonadism (76 versus 79 percent) and hyperprolactinemia (39 versus 39 percent) were unchanged. The rate of panhypopituitarism increased from 11 percent preoperatively to 35 percent after surgery. In comparison, transsphenoidal surgery was associated with little postoperative decrease in anterior pituitary function, and hyperprolactinemia resolved in 16 of 19 patients. Surgery and radiotherapy Following subtotal resection alone, the five-year local recurrence rate is approximately 50 percent . Postoperative radiation significantly reduces the risk of a local recurrence, but has little impact on survival, likely reflecting the success of RT in the salvage therapy of locally recurrent disease. The following illustrates the range of findings:

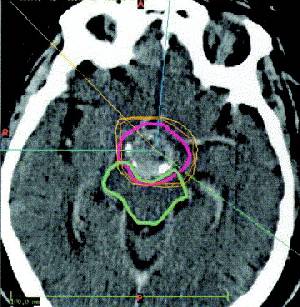

Several authors recommend radical subtotal resection and irradiation as an acceptable alternative to total resection . However, others advocate a more conservative (less radical) surgical approach, based upon the risks of aggressive surgery and the efficacy of radiation in this setting . Although patients can often compensate for neurologic and endocrine deficits, psychosocial deficits associated with radical surgery are now recognized as a major factor limiting the quality of life as young patients grow into adulthood . Thus, surgical hypothalamic injury should be minimized. To accomplish successful treatment without serious deficits, some have advocated an approach consisting of removal of no more tumor than is considered safe (ie, less than a radical subtotal resection), followed by postoperative irradiation. Patients may deteriorate acutely during radiotherapy; this is usually due to either cystic enlargement or hydrocephalus rather than tumor progression. If recognized early and appropriate surgical therapy is administered, radiation therapy can be completed with a good outcome . Radiation dosing Doses above 54 to 55 Gy provide a significantly greater likelihood of local tumor control . In a retrospective series, the recurrence rate was significantly higher in patients receiving <54 Gy compared with higher doses (50 versus 15 percent) . The incidence of radiation-induced endocrine, neurologic, and vascular sequelae is low unless doses above 61 Gy are administered . Another concern is the potential for late secondary malignant brain tumors in patients who have received cranial irradiation . Among eight patients who received radiotherapy for craniopharyngioma who developed gliomas, the mean radiation dose was 58 Gy and the mean latent period was 11.5 years . Cyst management Several other approaches are also useful in managing patients with craniopharyngioma initially or, more commonly, at the time of recurrence. Since recurrent symptoms are usually due to reaccumulation of cyst fluid, the following treatments can decrease cyst size: intermittent aspiration by stereotaxic puncture or placement of an Ommaya reservoir; sclerosis of the cyst wall by chemotherapeutic drugs; and internal irradiation with radioisotopes. Cyst aspiration Percutaneous aspiration of cyst contents has been used to alleviate symptoms, and intermittent aspiration may be recommended whenever total excision seems ill-advised. An alternative is placement of an Ommaya reservoir system for intermittent aspiration of cysts that cannot be completely resected. Intralesional therapy When repeated cyst aspirations are deemed inadvisable, intralesional radiotherapy or chemotherapy can be utilized. One case report described minimal excision plus intermittent intralesional bleomycin through an Ommaya reservoir in a child with a gigantic cystic craniopharyngioma . An alternative in patients with solitary or multicystic tumors is intracavitary irradiation via stereotactically applied radioisotopes . Beta-emitting isotopes such at 90Yt (yttrium-90), 186Rh (rhenium-196), and 32P are preferred because of the limited penetrance of the emitted energy and the relative ease of handling. The reported results are similar to those with microsurgery:

It has been suggested that intracavitary radiation results in better long-term psychosocial and pituitary functioning compared with other treatments. For this reason, the use of intracavitary radiation therapy has been recommended when more than 50 percent of the total tumor bulk is cystic, and when the number of cysts is three or less . The risk of subsequent visual deterioration is substantial . Recommendations We recommend removal of as much tumor as the neurosurgeon considers safe followed by external beam irradiation. Our approach to recurrent tumors depends upon the nature of the recurrence and the cause of the patient's symptoms. Cyst drainage procedures and occasional placement of radioisotopes are used when symptoms are due to a single large cyst; we consider further surgical removal when symptoms are caused by increased tumor size. PROGNOSTIC INDICATORS Craniopharyngiomas expand and damage the surrounding structures and have a tendency to recur even after "complete" removal , even when removal is guided by intraoperative MRI. Recurrences usually occur at the primary site or in contiguous areas rather than at distant sites. Cerebrospinal fluid seeding or distant metastasis is rare. Although histologically benign, these tumors shorten life and are better thought of as low grade malignancies. The 20-year survival rate of children with craniopharyngioma is approximately 60 percent; once recurrence occurs, this figure drops to approximately 25 percent. A multivariate survival analysis adjusting for age confirmed the importance of recurrence as a negative prognostic factor, although the 33 percent incidence of recurrence at ten years was not influenced by age, the extent of surgery, or postoperative radiotherapy . In this series, the 10- and 15-year survival rates were 68 and 59 percent, respectively, and the standardized mortality ratio compared to the general population was 5.6. The growth characteristics of craniopharyngiomas vary considerably. Some patients continue to lead symptom-free lives without therapy whereas others have continued tumor progression despite extensive treatment. Sudden onset of symptoms and rapid deterioration in a patient with craniopharyngioma is often attributable to expansion or rupture of cysts. It is difficult to predict a tumor's behavior at the time of diagnosis . However, certain clinical and pathologic characteristics do correlate with prognosis.

The prognostic importance of tumor type is controversial. One study noted a more favorable prognosis for the predominantly solid, noncalcified squamous papillary tumors, which occur more frequently in adults than do the more classic adamantinomatous variety. The overall behavior of the papillary subtype has, in some reports, been so different from the other craniopharyngiomas that some suggest that it be considered a separate entity. However, two larger series have found that these two histologic subtypes behave similarly with respect to resectability, sensitivity to radiation therapy, and overall survival . MANAGEMENT OF LOCALLY RECURRENT DISEASE Complete surgical resection is possible in 40 to 70 percent of patients with locally recurrent disease; however, reoperation results in a low cure rate and a high risk of morbidity . In contrast, radiation therapy, particularly three dimensional conformal radiation therapy or stereotactic radiosurgery, may provide good local control with a low incidence of complications. This was illustrated in a series of 14 children with recurrent craniopharyngioma following primary resection; seven underwent reoperation, five had radiation therapy, and two did not receive any treatment. Six of seven children with a second relapse had radiation therapy; of the 11 children who received radiation for either a first or second recurrence, four were treated with three dimensional conformal therapy and seven with stereotactic radiotherapy. After radiotherapy, the two and five-year second recurrence-free survival was 100 and 100 percent, respectively, compared to 43 and 0 percent, respectively, for surgery alone. Furthermore, reoperation resulted in significant intraoperative bleeding in three of seven patients, with permanent neurologic deficit in two. A role for postresection implantation of Gliadel wafers (carmustine embedded in a slow release matrix) has been suggested in patients with recurring aggressive craniopharyngioma, but experience is limited. |